Black performers seldom appeared on American television in the 1950s, so the only vintage Chuck Berry clips come from movies. This lip-sync of “You Can’t Catch Me” is from Rock, Rock, Rock (1956). Yes, he duck walks. He is introduced by Alan Freed.

Black performers seldom appeared on American television in the 1950s, so the only vintage Chuck Berry clips come from movies. This lip-sync of “You Can’t Catch Me” is from Rock, Rock, Rock (1956). Yes, he duck walks. He is introduced by Alan Freed.

Articles that end with confident assertions such as, “And that’s why Donald Trump is president,” are inherently suspect. A presidential campaign is a complex chain of events in which an almost infinite number of factors could have influenced public opinion by an amount greater than or equal to the margin of victory.

Consider this analogy. On the last play of the game, a football team is trailing by one point. Their kicker misses a relatively easy field goal from the opponent’s 25 yard line. Most spectators are likely to conclude that the missed field goal was the cause of their loss. However, if we were to watch a replay of the game, we might find dozens of offensive and defensive mistakes that, had they turned out differently, would have changed the outcome of the game. Picking any one of them as “the cause” of the loss is essentially arbitrary. It was the kicker’s bad luck to have failed on the very last play. Since it is readily available in everyone’s memory, people see it as the cause of his team’s defeat.

This is the first reason you should disregard the data I’m about to present and be skeptical of the claims that have been made for them.

An organization called Engagement Labs does market research in which they attempt—for a price—to measure consumer attitudes toward brand name products. They do this by asking an online sample of consumers to report whether they have had any positive or negative conversations about the product. The difference between the percentages of positive and negative conversations is their measure of consumer “sentiment” toward the product.

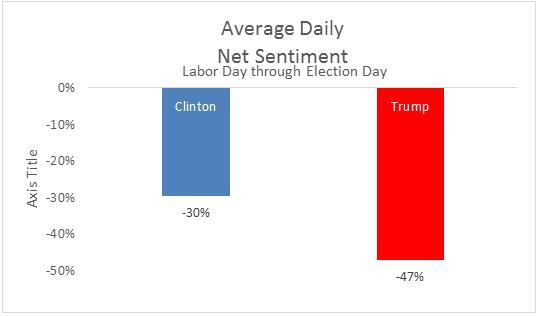

Every four years, out of curiosity, this organization asks their respondents to report positive and negative conversations about the two major party presidential candidates. Not surprisingly, Americans had negative attitudes toward both candidates. Averaged over the duration of the campaign (Labor Day to Election Day), attitudes toward Trump (-47%) were more negative than attitudes toward Clinton (-30%).

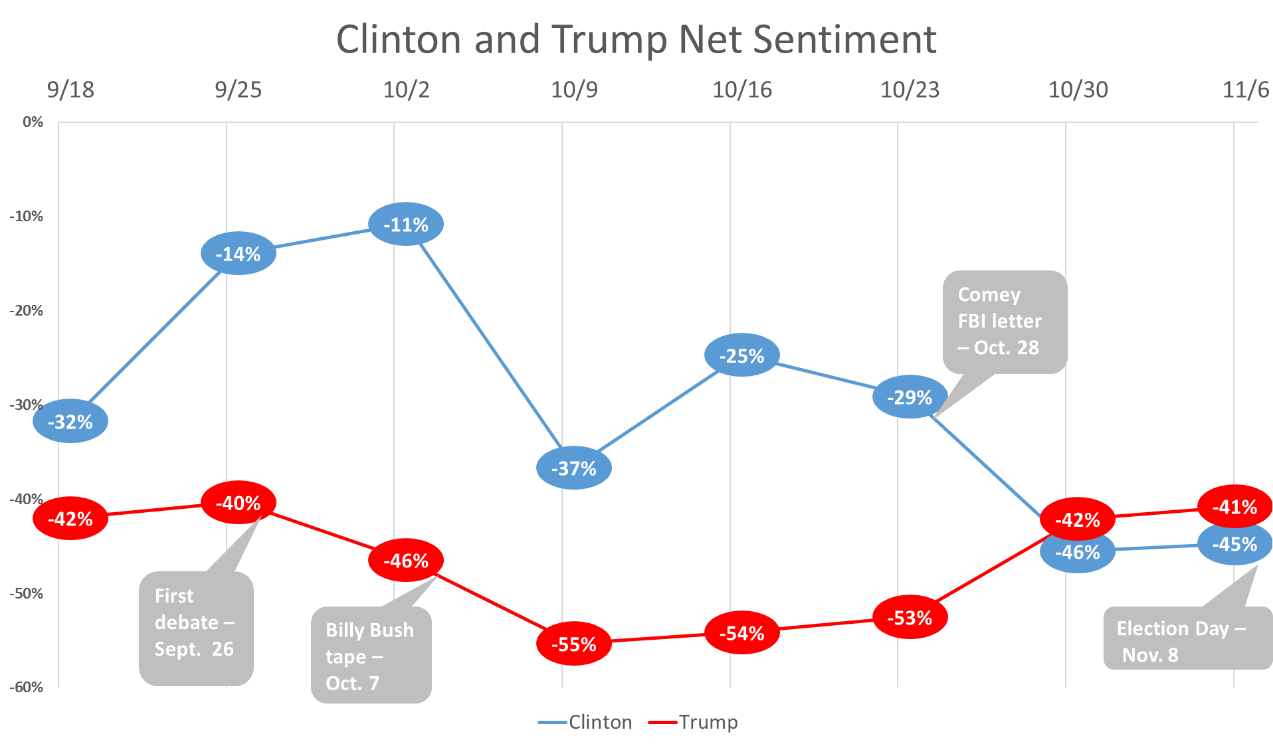

However, between the surveys conducted on October 23 and October 30, there was an abrupt change in their respondents’ conversations. October 28 was the day that FBI Director James Comey sent a letter to Congress stating that he was reopening his investigation of Hillary Clinton’s emails. Here are the data.

Two days after Comey’s letter, attitudes toward Clinton dropped by 17% and attitudes toward Trump increased by 11%—a 28% shift, sufficient to put Trump ahead. Trump maintained that slight edge on November 6, two days before the election.

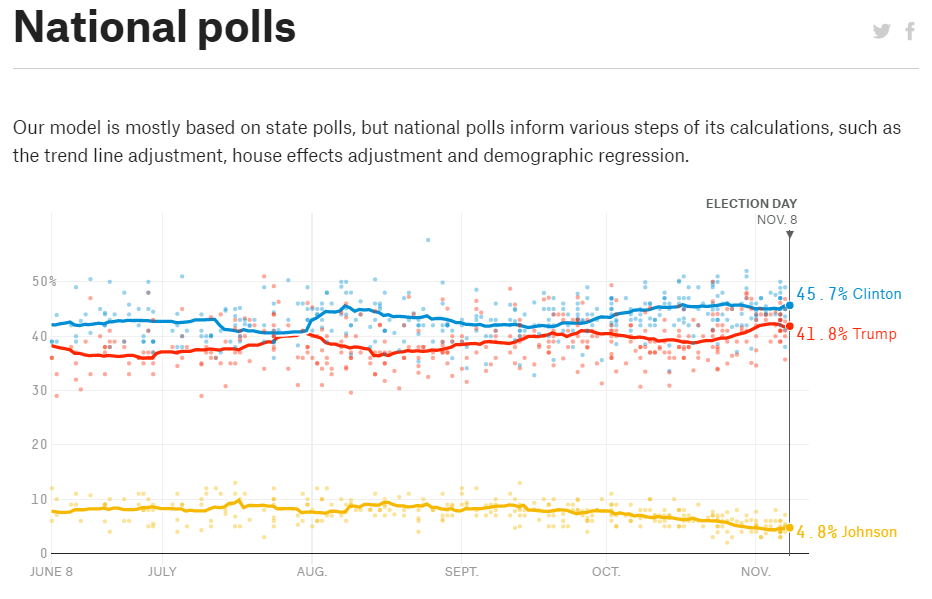

This is an astonishing change in attitudes. Such a large shift is almost never reported in pre-election surveys. Here’s the average of pre-election polls conducted by traditional methods.

Why didn’t other pre-election surveys report this abrupt shift in attitudes following Comey’s letter? Brad Fay, Chief Commercial Officer of Engagement Labs, maintains that their measure of political sentiment is a more sensitive predictor of election outcomes than the typical survey question which asks respondents for whom they intend to vote. He gives four reasons.

As a social psychologist, I accept Fay’s first argument. Attitudes don’t always predict behavior very well. However, past behavior is a relatively good predictor of future behavior. In this case, the behavior of stating your opinions to friends can encourage you to behave in a way that is consistent with those opinions. Fay’s last three reasons are semi-redundant. They are different ways of saying that our behavior is influenced by the attitudes of our peers.

However, there is a second reason you should be skeptical of the information in this post. I’ve searched the Engagement Labs website in vain for basic information about how their surveys were conducted—their sample size, their method of ensuring the representativeness of their sample, the wording of their questions, etc. All I can find is jibberish such as “(t)he data are fed into our TotalSocial platform, where it is scored and combined with social media data to capture the TotalSocial momentum for leading brands.” They probably regard this information as a trade secret. But until such information is provided, I’ll have to claim that this is an intriguing finding of uncertain validity.

You may also be interested in reading:

Norway is the world’s leader in use of zero-emission, fully electric vehicles (EVs). They have 100,000 EVs on the road, over 5% of Norway’s cars. Thirty-seven percent of the new cars purchased in Norway last year were EVs. Norway’s transportation minister anticipates that the number of EVs on the road will rise to 400,000 in 2020, and that the sale of fuel burning cars will end by 2025.

There’s a good reason for these trends—incentives. EVs are exempt from Norway’s value-added tax, which adds 50% to the cost of a new vehicle. They are also exempt from road tolls and tunnel and ferry charges. And they get free parking, free charging and the freedom to use bus lanes. These incentives have been so successful that Norwegian politicians are rolling them back. The value-added tax will soon be replaced by a subsidy, which may eventually be phased out. EV owners will have to start paying 50% of the state road charges in 2018, and local authorities are now free to curtail free parking, local tolls, and the use of bus lanes.

Norway isn’t the only place where EV sales are booming. There were over two million electric cars on the road by the end of last year. Here’s the world-wide trend. How good are all-electric vehicles for the environment? Very. This video reports the results of a recent analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

How good are all-electric vehicles for the environment? Very. This video reports the results of a recent analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

What about the price? The average price of a new car is $31,000. To be competitive, the cost of an EV must drop to between $25,000 and $35,000. A new Tesla costs $35,000 and a Chevy Bolt sells for $37,5000. The prices are dropping due to a combination of mass production and the decreasing cost of batteries. This analysis by Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects the future trends in the cost of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) in thousands of dollars (on the left) and the percentage of Americans willing to buy at those prices (on the right).

Currently, Americans can get a federal income tax credit of up to $7500 for purchasing an EV, but there are conditions. This chart summarizes the current status of federal and state incentives, some of which expired at the end of last year.

You may also be interested in reading:

The other day in California, last week, a woman, 66 years old, a veteran was killed, raped, sodomized, tortured and killed by an illegal immigrant. We have to do it! We have to do something! We have to do something!

Presidential candidate Donald Trump

Judgmental heuristics are the simple rules or mental shortcuts that people use to make decisions quickly and efficiently. One of those rules is the availability heuristic, which states that the frequency of an object or event is judged on the basis of the number of instances retrieved from memory and the ease with which they come to mind. The easier it is to think of examples, the more frequent the object or event is assumed to be.

The availability heuristic often leads to correct inferences. In the northeastern United States, robins are in fact more common than other birds. But availability can be misleading. For example, when estimating the frequency of various causes of death, people overstimate dramatic events such as homicides and traffic accidents and underestimate less public illnesses such as strokes and diabetes. The presumed explanation is media salience. Estimates of the frequency of causes of death are highly correlated with space devoted to types of death in recent newspapers.

The availability heuristic is one explanation for for a common cognitive error known as the base-rate fallacy. This refers to a tendency to overgeneralize from individual examples while ignoring statistical base rates. A specific case is more emotionally interesting and easier to remember; it is more available. A statistical statement is not as interesting. Base rates are usually underweighted, and sometimes completely disregarded, especially when specific instances are available. It follows that if propagandists want people to overestimate the frequency of an event, they should publicize examples of that event, preferably with vivid pictures and lots of memorable details.

Availability biases can influence social policy. An availability cascade is a self-sustaining chain of events that starts with a small number of cases that are heavily publicized by the media, leading to public panic and large-scale government action. One goal of terrorism is to start availability cascades. An availability campaign occurs when some pressure group, for altruistic or self-interested reasons, tries to instigate an availability cascade.

I was reminded of this by last Tuesday night’s address to Congress when President Trump introduced four alleged victims of crimes committed by immigrants who were seated in the audience and announced an executive order creating an office called Victims of Immigration Crime Engagement (VOICE) within the Department of Homeland Security, whose purpose is to make public “a comprehensive list of criminal actions committed by aliens.” (He didn’t say that the “aliens” had to be in the country illegally.) Right-wing news organizations have been heavily reporting real or fake crimes committed by immigrants for several years.

Apparently the President thinks that one way to increase support for his immigration policies—the wall along the Mexican border, mass deportations, the Muslim ban—is to induce Americans to overestimate the frequency of crimes committed by immigrants. To this end, he is starting an availability campaign.

What is the actual base rate of crimes by immigrants? Research consistently shows that immigrants commit crimes at a lower rate than native-born Americans. Robert Adelman and his colleagues analyzed data from 200 metropolitan areas from 1970 to 2010. They found that as immigration increased, rates of murder, robbery, burglary and larceny decreased, and rates of aggravated assault remained the same.

In a forthcoming study, Charles Kubrin and Graham Ousey conducted a meta-analysis combining the results of over 50 studies examing the relationship between immigration and crime published between 1994 and 2014. Their conclusion: “More immigration equals less crime.” However, the rate of crime by second generation immigrants–that is, the children of immigrants–does not differ from than of other Americans.

Kristin Butcher and Anne Piehl studied why immigrants commit crime at lower rates than non-immigrants. They concluded that people who self-select to immigrate to the U. S. are less criminally active than the native born population, and are more responsive to deterrents to crime, such as the threat of a jail sentence.

Kristin Butcher and Anne Piehl studied why immigrants commit crime at lower rates than non-immigrants. They concluded that people who self-select to immigrate to the U. S. are less criminally active than the native born population, and are more responsive to deterrents to crime, such as the threat of a jail sentence.

This is not the only instance in which the president has presented misleading information apparently intended to persuade us that the exception is the norm. He has criticized the media for “underreporting” acts of terrorism by Muslims, when in fact the opposite is the case. In last week’s address, he cited an unrepresentative 116% increase in health insurance premiums in Arizona to support his claim that the Affordable Care Act was failing.

Trump’s behavior is a classic example of scapegoating. Scapegoating refers to the singling out of an individual or group for blame that is not deserved. Scapegoating is presumed to be responsible for the increase in prejudice and violence toward already stigmatized minority groups during economic hard times.

Until 1938, it was the policy of Hitler’s Ministry of Justice to forward all criminal indictments of Jews to the press office to be publicized. With VOICE, the U. S. now has its own government-run ministry of propaganda given the mission of convincing us of something that isn’t true—that immigrants commit more crimes than native born Americans.

You may also be interested in reading:

So Far, It Looks Like It Was the Racism