One question has dominated the conversation among political scientists attempting to explain the presidential election: Were Trump’s supporters motivated primarily by economic anxiety or racial resentment? So far, I’ve avoided weighing in on this question, hoping that the definitive study would appear. It hasn’t yet, but a new experiment by Michael Tesler is interesting enough to warrant giving you a progress report.

The corporate media narrative clearly favors the economic explanation. In a typical article, we are told (correctly) that the family incomes of working class families have been stagnant for 35 years, that trade agreements and the 2008 recession have caused widespread unemployment and underemployment, and that both political parties have ignored the plight of these Americans. This is followed by interviews with a couple of Trump supporters who express pain and anger over the way they have been treated. However, this is anecdotal evidence. The answers given by Trump supporters are partially driven by the questions they are asked. For the media, framing the election in terms of economic anxiety rather than racism avoids offending Trump and his supporters.

Much of the evidence available prior to the election failed to support the economic anxiety narrative. Surveys showed that racial attitudes predicted Trump support better than economic attitudes—for example, these two, and this one. This large sample Gallup poll also cast doubt on the economic explanation. The median household income of a Trump supporter in the primaries was $72,000, higher than the median income of Clinton supporters ($61,000) and the general population ($56,000). In addition, post-election analyses showed that Clinton received more votes in economically-distressed communities—those with a higher percentage of their population below the poverty line.

Michael Tesler has been studying the racialization of politics for over a decade. Racialization refers to the tendency of racial attitudes to influence opinions toward a variety of other issues not obviously related to race, such as health care or gay marriage. Tesler embedded an experiment within a YouGov/Huffington Post national survey of 1000 voters conducted on December 6 and 7. Half the participants were asked if they agreed with the following statement:

Over the past few years, Blacks have gotten less than they deserve.

Ths is an item from the Symbolic Racism Scale, which is used to measure racial resentment. The remaining respondents were presented with this statement.

Over the past few years, average Americans have gotten less than they deserve.

Most people assume an “average American” is White. In 2005, Devos and Banaji conducted a series of five studies showing that the category “American” is more strongly associated with the category “White” than either “African-American” or “Asian-American.” Based on this evidence, Tesler assumed that respondents would interpret the second statement as referring to Whites. He then compared the responses of people who reported that they had voted for Clinton and Trump to these two questions.

This study pits the economic anxiety and racial resentment explanations against one another. Would Trump voters be more likely than Clinton voters to agree that average Americans have gotten less than they deserve? Or would differences emerge only when the question referred to Black Americans?

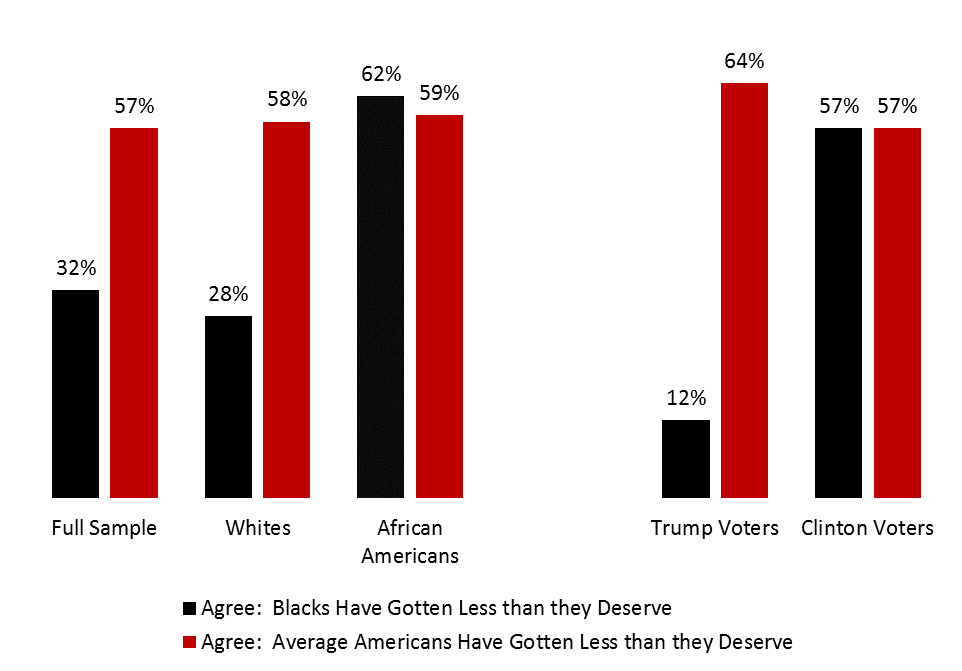

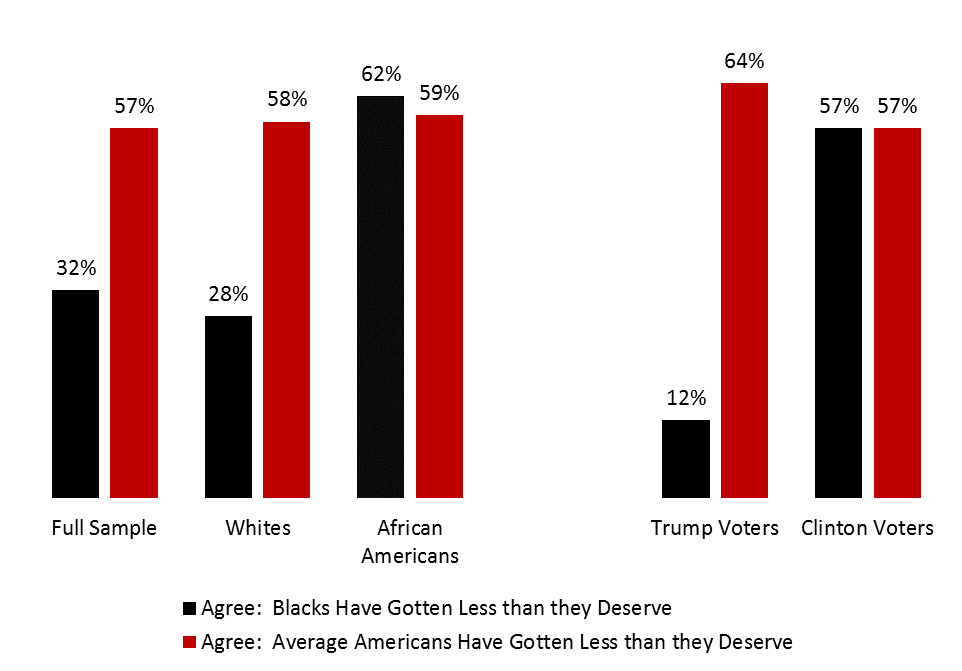

The results on the left show a typical racial divide between Black and White respondents. White participants were more than twice as likely to think that average Americans had gotten less than they deserve than to think that Blacks had gotten less than they deserve. Black participants thought everyone had gotten less than they deserve. Since there were more White than Black participants, the averages for the full sample resembled those of Whites.

The data on the right address the research question. Clinton voters were almost as likely (57%) to say that average Americans have gotten less than they deserve as Trump voters (64%). Since this was a large sample, this 7% difference is probably statistically significant, but it is small in comparison to the difference on the racial resentment item. Only 12% of Trump supporters agreed that Blacks had gotten less than they deserved, compared to 57% of Clinton supporters—a difference of 45%. The data are more consistent with the racial resentment interpretation of Trump’s victory.

Tesler frames the responses of Trump supporters as an example of the ultimate attribution error. Attribution is the processes by which we infer the causes of behavior. The ultimate attribution error is the tendency to take personal credit for our own successful behavior and that of our in-group, and blaming our failures on environmental obstacles, while at the same time blaming members of out-groups for their failures, and attributing their successes to unfair advantages. Given this bias, it follows that Whites have gotten less than they deserve, while Blacks have gotten more.

Were the election results caused by economic anxiety or racism? We still await a more definitive study. It will require a larger sample of voters and a valid measure of economic anxiety, with statistical controls for other variables known to influence voting decisions. If I see such a study, I’ll let you know.

You may also be interested in reading:

Trump’s Trump Card

What Does a Welfare Recipient Look Like?

Framing the Debates

You must be logged in to post a comment.